by: Jamal Al Shalabi, Rasha Istaiteyeh | Hashemite University

Until late 2022, more than 670,000 people from Syria had sought refuge in Jordan, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), with over 85% of Syrians living outside refugee camps in rented accommodations. According to the Refugee Commission, Jordan also hosted asylum seekers and refugees from other countries during 2022, including 65,854 Iraqis, 12,934 Yemenis, 5,679 Sudanese, 651 Somalis, and 1,379 individuals from other countries.

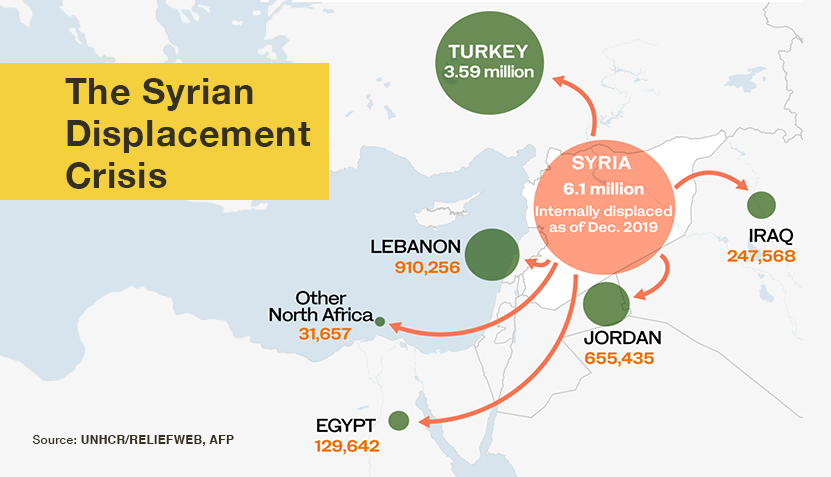

Based on this official data from a significant international organization, Jordan is considered one of the most welcoming countries to refugees in the world, considering its geographic size (89,000 square kilometers), a population demographic of 6.249 million , and a national income that does not exceed US$4,400 per person in 2023, which places it among the low-middle-income countries for 2024. The Syrian crisis emerged in 2011, representing a new humanitarian and political challenge for this small country, especially with nearly 5 million Syrian refugees fleeing not only to Jordan but also to neighboring countries: Turkey and Lebanon.

Jordan’s experience with refugees

Historically, Jordan has a “significant legacy” of hosting refugees due to its important geopolitical location. Circassians, Chechens, and Armenians left the Caucasus region and settled in the Ottoman Empire, which became part of the Emirate of Transjordan in 1921. Jordan also hosted Palestinian refugees following the Arab-Israeli wars in 1948 and 1967. Due to the civil war in Lebanon in 1975, Jordan began to welcome Lebanese refugees again. The same situation occurred during the invasion of Kuwait in 1991, when approximately 300,000-400,000 Jordanians and Palestinians were displaced. This was followed by a massive influx of Iraqis after the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, along with the ensuing sectarian violence between 2004 and 2007.

And so, the new wave of Syrian refugees reaffirms Jordan’s role in welcoming those fleeing the ongoing war and destruction since 2011 to the present day. Currently, Jordan is hosting approximately 1.4 million Syrian refugees according to the Jordan Response Plan for 2016-2018, distributed across three camps: Zaatari, Azraq, and Zarqa, which accommodate 80,000, 34,000, and 6,000 respectively. However, the majority of Syrian refugees reside in Jordanian cities and villages, with their number reaching 1.27 million refugees; this means that the ratio of “refugee-to-citizen” in Jordan is the highest in the world. The Jordanian monarch King Abdullah II pointed out this fact at the donors’ conference in London on February 3, 2016, stating that “the number of refugees residing in Jordan is much greater than their number in all of Europe“; this implies that one-third of Jordan’s population consists of refugees!

Jordanian generosity without “Legal References”

The striking thing about Jordan’s somewhat “generous” approach is that the Jordanian state does not yet have an international legal framework that regulates government policies towards refugees. Jordan has not signed any international agreements or protocols regulating refugees, including the 1951 United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees regarding rights, duties, and freedoms, and the 1976 additional protocol.

Despite this fact, Jordan is a party to many other human rights treaties that impose similar direct obligations regarding the rights of refugees; Jordan is a party to the “Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment” of 1984, which states in Article 3 that “no State Party shall expel, return (refouler) or extradite a person to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.” This provision applies to Syrian refugees, especially with multiple international reports documenting cases of torture in Syria by various parties involved in the conflict.

Jordan is also a party to the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which protects the right to freedom of movement, legal procedures, and the prohibition of arbitrary detention. Jordan is part of the “Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination” and “Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination” agreements from 1965.

All these international legal references related to the rights of refugees are, in principle, consistent with Jordanian domestic law, which does not contain any provisions that contradict what is stated in international agreements and protocols regarding refugees. This includes Article 21 of the Jordanian Constitution of 1952, which states, “Political refugees shall not be extradited on account of their political beliefs or their defense of freedom.” Therefore, Jordan recognizes anyone crossing the border from Syria as a “refugee,” as it has relied on an “open border policy” with Syrian refugees since the beginning of the crisis, exempting them from visa requirements for entry and residence permits. Syrians can enter Jordan, but they must obtain a valid card from the UNHCR to access assistance and public services.

In practice, Jordan’s policy towards refugees relies heavily on the “Memorandum of Understanding” established between Jordan and the UNHCR in 1998 and its amendments in 2014. Although this agreement does not impose legal obligations on Jordan, it sets the governmental political frameworks for addressing refugee issues. According to this memorandum, Jordan provides “temporary residence for refugees while awaiting a permanent solution elsewhere,” with the Commission and other NGOs “offering assistance to refugees,” while the Jordanian government facilitates access to health and educational services and many other benefits. The same definition of “refugee” as per the 1951 Refugee Convention applies to the memorandum of understanding, without geographical or temporal limits, even though Jordan is not a signatory to this treaty. Moreover, the Jordanian government has agreed to uphold its commitments to non-refoulement, non-discrimination, and ensuring the right of refugees to work. According to the Jordanian Ministry of Labor, Syrian refugees were given priority over other foreign nationals in applying for work permits at the onset of the crisis. They also have the right to access the courts, and are exempt from fines for overstaying their residency and departure fees.

Conclusion

Although the Jordanian government has relinquished a significant amount of control over the refugee situation to the UNHCR in the memorandum of understanding, the government sector still retains its role in addressing the needs of refugees through the Ministry of Interior. The ministry is required to provide staff and technical assistance to the UNHCR to enable the latter to carry out status determination and resettlement, as well as to assist the UNHCR in managing the camps.

With the expansion of violence in Syrian territories and the changing control over the official Syrian-Jordanian border crossings by various parties, Jordan has established 25 official crossing points along its 378-kilometer border with Syria, in addition to 33 crossings that open depending on the situation. This is in accordance with residency and foreign affairs regulations, which allow for exemptions related to international or humanitarian responses or political asylum rights. Typically, the Jordanian authorities prioritize the injured and sick, followed by children (especially those unaccompanied by adults or minors), the elderly, and finally adults. Children make up 41% of incoming refugees, women account for 30%, and men make up 29%.

The important question remains: what impact do these “new” migrants have on the economy of a community that is already poor, weak and dependent on external support?